He fled his native country with his group, the Walias Band, in 1981 and now drives a cab in Washington DC, in which he also composes. But, despite his lo-fi setup, “if you have a good bassline you can create anything”

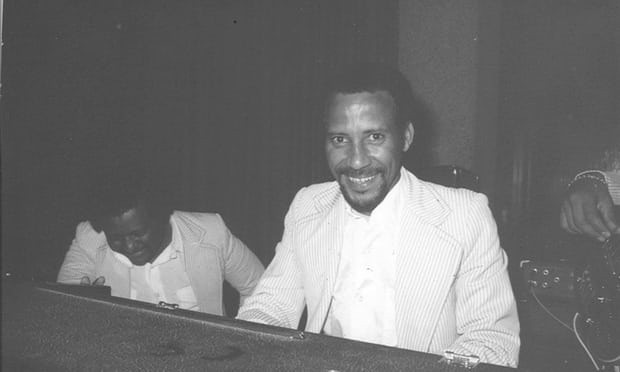

On a Monday afternoon, Hailu Mergia is driving through the suburbs of Washington DC, his laminated cabby licence tacked to the back of his seat. It’s rare that one of his customers realises that their driver is an Ethiopian musical legend, the keyboardist and accordionist of the Walias Band, one of the most popular groups from the country’s 70s golden age. When Mergia speaks of that era – growing up near Addis Ababa, raising goats and sheep, singing traditional folk music, joining the military, forming the Walias Band and eventually leaving Ethiopia for good – the dates get fuzzy, but the experiences remain clear.

He is not even sure how old he is – either 71 or 72. When he was born, birth certificates weren’t always issued. He wishes that he had footage of the Walias Band’s 12-hour concerts at the Addis Ababa Hilton hotel: all-nighters for club-goers seeking refuge during the curfews that Ethiopia’s Derg government enforced for 16 years. “Maybe we didn’t care,” he says, “or maybe we didn’t think we’d get this far.” By “this far”, he means his new album – his first in more than 30 years. Mergia slides the CD of Lala Belu into his cab’s stereo and presses play on some of his most incandescent and exploratory music. As we drive past faceless strip malls, warm, brushing chords and accordion fill the air, Ethiopian pentatonic rhythms mingling with American bop and fusion.

Mergia’s car is a good place to hear his new music because it’s where he writes it. “After I drop my customer, I grab my keyboard from the trunk and sit in the car and practice,” Mergia says. Since 1998, he has been picking up fares from Washington’s Dulles airport; he spends the downtime in the company of his battery-powered Yamaha. “When I compose, I record it with my phone. I do it with my voice, whistling, whatever; and then I put it on the keyboard and record it in my car. I send it to the other musicians in my trio: ‘Learn this line.’” Mergia pauses and smiles. “I always think: if you have a good bassline you can create anything.”

The perfect groove has steered Mergia since the Walias days. The band’s eight members had each worked in the city’s bustling scene – playing for a few dollars on borrowed instruments at whichever club paid the most. They agreed to become a group, pooling their earnings to buy their own gear. “We were an equal band,” Mergia says. “Everyone got paid the same, everyone took turns as the bandleader. Everyone dressed sharp. We each had three suits. We wore black and white.” They named themselves after an endangered species found in the mountains of Ethiopia, and, as their popularity grew, so did the duration of their shows.

At the Hilton, they had to adapt to broad international tastes. From 7pm to 10pm, it was dinner music for the diplomats and rich globetrotters: “Stranger in the Night; New York, New York; Yesterday,” Mergia recalls. “Japanese songs, French songs – even Je t’aime, Moi Non Plus – and Arabic songs.” Then came the dance crowd, prompting the Walias to tap into their love of the soul and jazz records that friends brought back from their travels; they improvised on melodies by James Brown and Booker T and the MG’s. (Mergia still thinks Green Onions contains the world’s best bassline.)

Recorded music was strictly controlled by the Derg government. “Any song you wanted to release, you had to first take it to the minister of information; if the lyrics were not acceptable, you could not release it,” Mergia recalls. In 1979, he recorded an album of pro-revolution songs that he had collected during the first five years of the regime. The government took a liking to them, he says, distributing them as gifts to diplomats, and invited the Walias to play a state dinner. “When I listen to it now, I have so many memories,” Mergia says. “The good, the bad. You have to memorise the bad times, too.” Half a million Ethiopians were killed under the Derg regime. Mergia left Ethiopia with the Walias in 1981, as the country entered a devastating famine, and he has only returned for visits since.

Shortly after their first tour in the US, the original Walias Band broke up. They had become a family as well as a business and creative project. “It was a hard, hard day,” says Mergia. He recorded his first solo album, Hailu Mergia and His Classical Instrument, in 1985, during the tough period that followed in Washington. “It came out of a time of being really alone,” Mergia says. It’s a contemplative album, just Mergia in the studio. “The accordion and the Rhodes [piano] were old, the Moog was a new instrument,” Mergia says. “I really liked it, the mix of those vintage and modern sounds.”

He released Classical Instrument on cassette and played a few concerts in Paris, London and Addis Ababa, but in 1991 he stopped performing. “I don’t know why,” he says. “I never gave up playing music – I just didn’t play in a club.” With friends in Washington’s growing Ethiopian community, he opened a restaurant. Six or seven years later, he bought his first taxi. Along the way, he reconnected with a girlfriend he hadn’t seen since his youth in Ethiopia and they got married.

Mergia drives to their suburban house, which is filled with portraits of his wife, Ayu Abegaz, and photos from the old days. In the basement, his Rhodes piano and drum set are set up for weekly practices with his local trio. Abegaz collects new Ethiopian music, but Mergia prefers his old vinyl – Count Basie, Gladys Knight, Oscar Peterson and his beloved Frank Sinatra. “The Lady Is a Tramp – I love that one! My favourite is old jazz. Maybe because I am old!”

Brian Shimkovitz, a music blogger who started the reissue label Awesome Tapes from Africa, came across Classical Instrument in a cassette bin in Ethiopia and was hooked. When Shimkovitz rereleased the album in 2014, Mergia was invigorated enough to tour again and to write new songs. Lala Belu was recorded in London with drummer Tony Buck and bassist Mike Majkowski; Mergia took it back with him to DC for “the colouring parts”.

Back in the cab, Mergia cues up Lala Belu again. “What I want now,” he says out of the blue, “is for someone to help me tell my story, my whole life.” He points his taxi back over the bridge to Maryland and the stereo lights up on cue.

Source: The Guardian

By: Rebecca Bengal